Volunteer activities on North Island

Volunteer activities

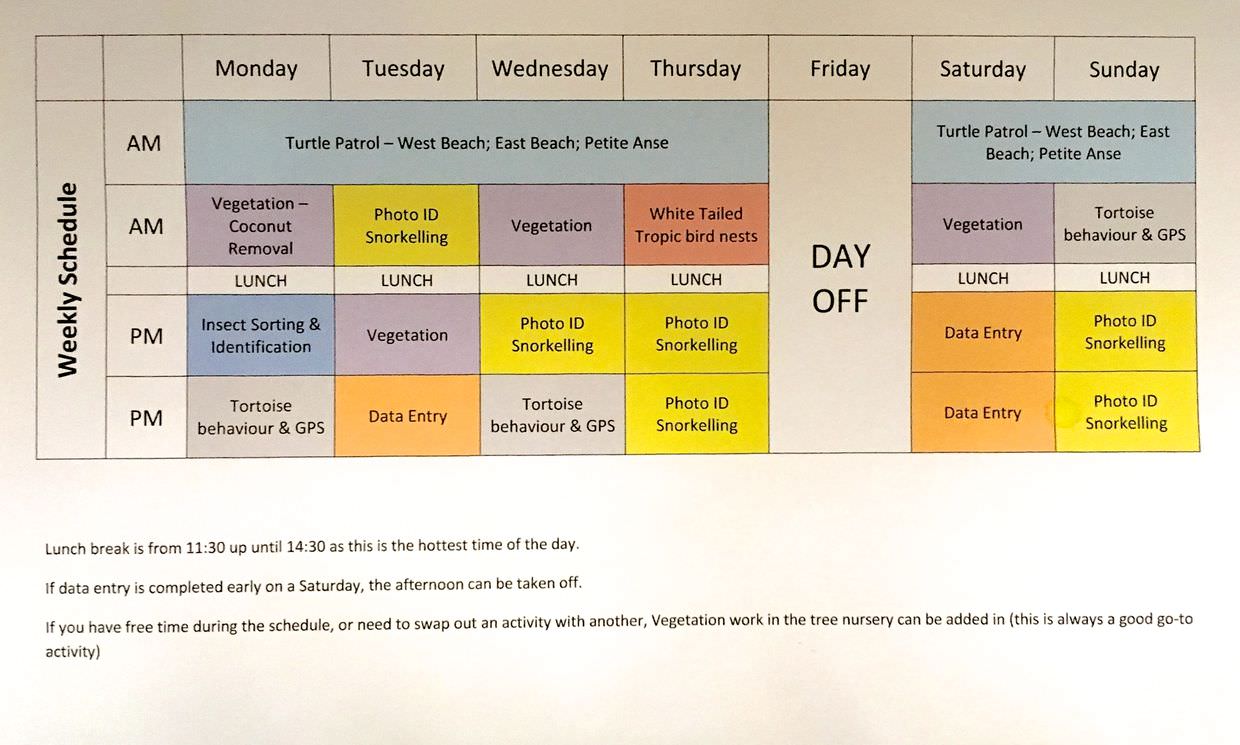

Each day is broken up into 4 loose slots; two morning sessions, two afternoon sessions and 2h30 for lunch – it’s so hot at midday all you can do is rest. The morning sessions begin at 7am, which sounds early but is the nicest time of day, half an hour after dawn, when the air is still comfortably cool.

“Island time” means the slots don’t last as long as they should, or start later, or they get swapped around, or there’s simply no activity to do (ie no data to enter); it’s all very relaxed, well, until something overruns or someone can’t do something because they don’t have a buggy, or a GPS, or some other vital tool – and then everyone gets a bit tense for a little while.

Turtle patrol

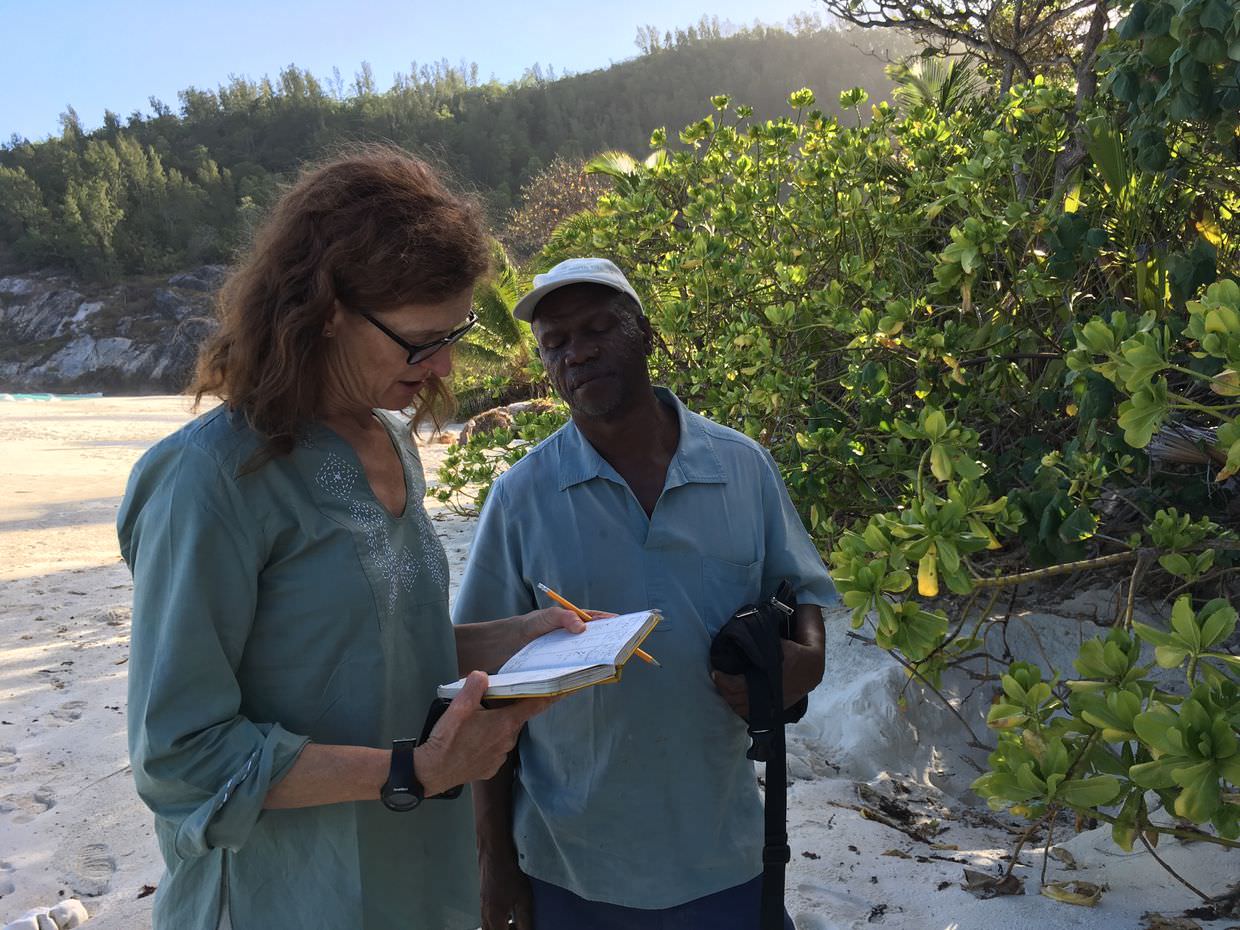

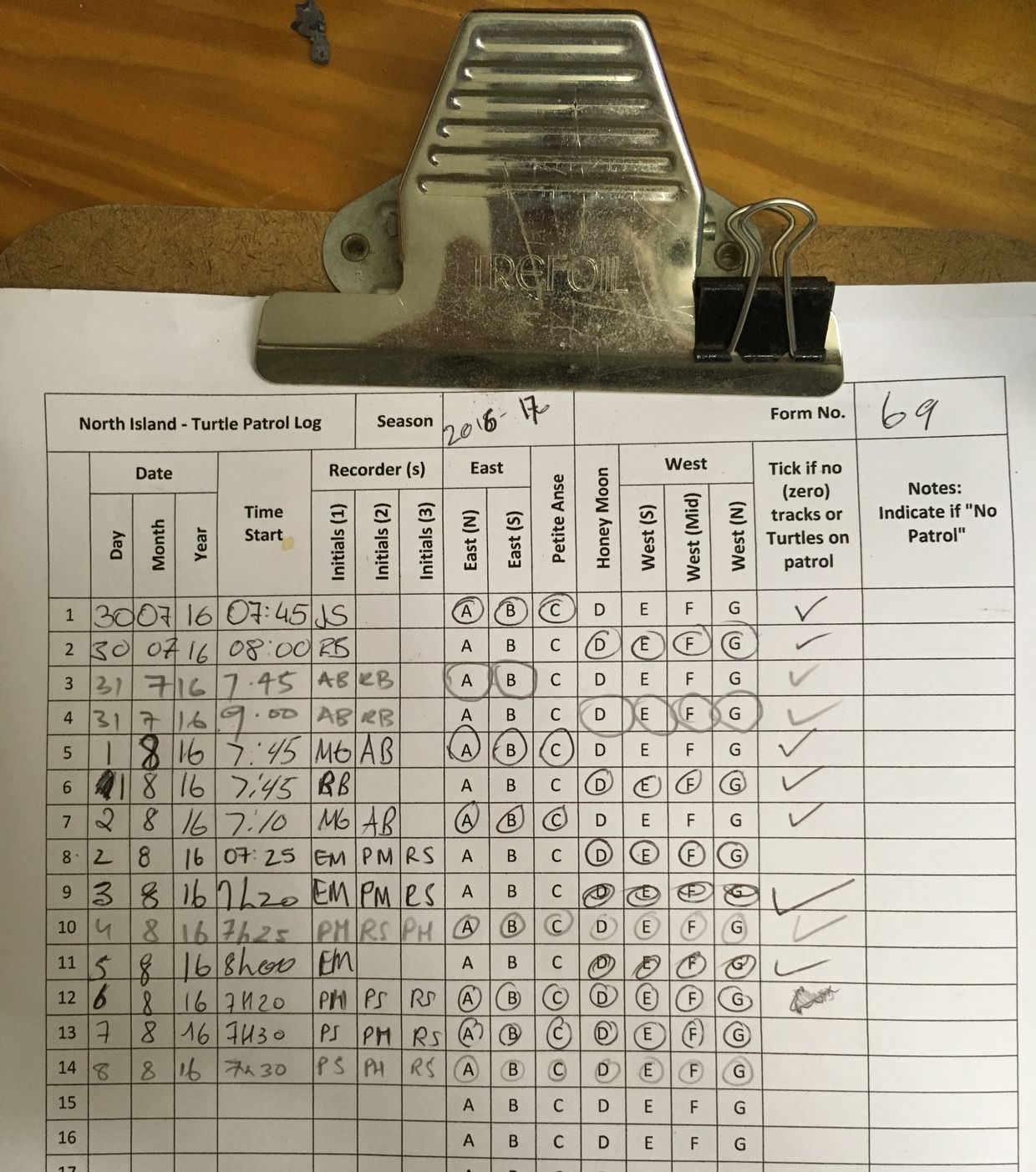

This is my favourite activity on North Island, and it’s the first activity every morning. After breakfast we take the buggy, and split up, heading out to each of the islands four beaches. Our job is to walk the beach, to see if any turtles have emerged overnight; we take with us a bag for rubbish, and a pack of tools incase a turtle did visit; a log book, a GPS recorder, a tape measure, and a marker pen. (There’s one pack for four people and four beaches, so if there’s lots of activity it can take a while).

If a turtle has emerged it’s obvious, there’s a track that comes from the sea, probably leading to a body pit or a nest site, and then back again. In August it’s predominantly green turtles that are nesting, the island has both green turtles and hawksbill turtles, but typically when one is laying, the other isn’t; that’s what the data collected by volunteers shows.

A green turtle can weigh about 200-300kg (whereas the hawksbill is closer to 70kg), and it leaves tracks about 1m across. We use the tape measure to get an indication of their size. Green turtles typically emerge overnight, presumably so their large body can stay cool and they don’t get caught out in the hot sun, it also meant I didn’t see many turtles; visiting during hawksbill season means you see loads of turtles.

When a turtle finds a spot they dig to create a body pit and an egg chamber, up to a metre deep, to lay their eggs. Green turtles lay 100 or so eggs at once, not all of them fertilised. While laying eggs the turtles are in a trance like state, they continue until all eggs have been laid. This is the point at which a turtle can be tagged with a titanium metal identifier. After digging and laying they cover the eggs and spend a long time disguising where the nest is. They throw sand in all directions and make disturbances in the sand. The disguise is mostly to prevent their eggs from being predated by crabs.

There are no signs of digging to cover up a nest.

Crabs swarm around disturbances in sand, looking for a meal. Around many nests there are crab holes, but they don’t always find the eggs; this predation is natural and is not prevented. Sometimes you can find the egg shells lying on the beach where crabs have gotten to them and dug them up. I enjoyed walking through the sand, then doubling back to see the island’s ghost crabs investigating my footprints.

When we find a nest we mark it with wooden stakes, and on a coconut write the species of turtle, the nest number and the date. Then we save a GPS location for it.

Note the crab trails in the bottom of the image.

Some turtle digs get abandoned and we don’t find a nest – the sand might be too soft, and keep falling back in, preventing the pit from being deep enough, or it might have obstructions like plant roots, in these cases a turtle will usually abandon its effort and return to the sea without laying. One particular turtle however made a mammoth effort, she climbed the beach and began digging, but the site wasn’t right, so moved on, she made 5 attempts, and left a turtle track over 100m long; the turtle must have been exhausted – at one point, after 3 digs, it looked like she was heading back to sea, but she doubles back again to try twice more, all unsuccessful; poor thing. We still save a GPS location, but mark it as an emergence rather than a nest.

On our busiest day we had 3 nests and 6 emergences to log, across the island. But we also had many days when there were neither. After a drunken night at a staff party, sometimes you find yourself wanting the latter, just so you can return to bed.

With some dedication, we were also fortunate enough to see some green turtles (page 3).

Tortoises

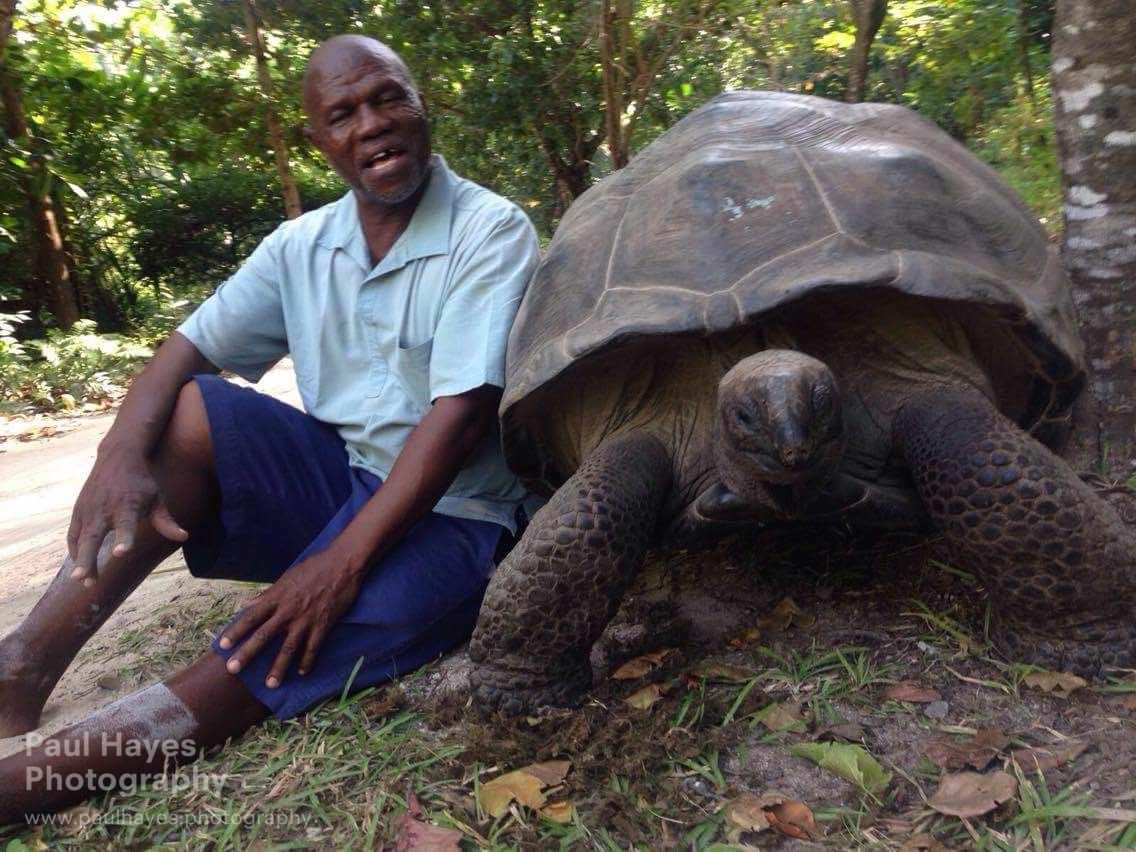

The giant aldabra tortoises on North Island are adorable, there are over 80, with three dominant males; Patrick, Harry and Brutus – each about 150 years old. If you surprise them (they’re easily scared), they quickly shrink back into their shell and breath out quickly, making the sound of a deflating balloon. By the volunteer house there’s a pen for the young, they’re about 2 years old and kept out of harm’s way (ie road accidents).

As a volunteer it’s our job to regularly find as many of the tortoises as we can. When found we note the number on their rear, we then GPS tag their location, and indicate their current activity – eating, resting, “active”, etc. The numbers are etched into their shells, but many of them are illegible.

Each tortoise has its own personality. Number 38 likes to hang around the volunteer house, often drinking from the leaky tap out the back. Patrick is an enormous, friendly giant that likes to sit around in the staff village, whereas brutus is a brute, and is altogether a lot more grumpy.

Living on the island, you come to love and accept these creatures, which you find all over, doing their thing; chilling in the marsh covered in mud, munching on dried leaves, drinking from one of the water holes, striding across the plateau in search of shade, sleeping, or receiving fruit from staff outside the bistro.

Snorkelling

The reefs are ideal for snorkelling, but the activity depends on the weather, the sea’s roughness and visibility in the water. While snorkelling is often seen as a recreational activity for volunteers, there is some work here too; there’s a compact camera with a waterproof case that should be taken out and used to photograph the variety of fish species around the coral. Back at the environment office the species can then be identified and saved in a spreadsheet along with their pictures.

As a poor swimmer, and with waves that often break above my head, I opted out of the snorkelling – one particular wave flattened me and I almost lost flippers and mask. I’m not confident enough to swim out to the coral without a lifeguard or anyone on watch, in case I get into trouble. This is kind of a bummer, as water is the best way to cool down in the stifling heat, and the island’s best wildlife is in the surrounding reefs. Many volunteers also take part in dive training, and some have taken the open water exam here. But that’s all too advanced for me; I’d prefer calm water with a shallow gradient to find my bearings, or a pool.

Vegetation

Just behind the volunteer house lies a tree nursery where Elliot (tree Elliot, not turtle Elliot) grows all the baby tree species, nurturing and preparing them to be planted somewhere on the island.

As volunteers we aided this effort by planting and re-planting trees, taking saplings and cuttings that have taken root and moving them to larger quarters.

Around a wheelbarrow full of soil we’d fill “plastics” with the brown stuff, put a hole in the middle and insert a stick with leaves, pat it down, and start on the next. It’s not glamorous, but in a single session four of us could plant 150 trees.

Trees like deckenia nobilis (millionaire’s salad palm), a protected species of palm tree with a thorny trunk, its endemic to the Seychelles and grows up to 40 metres tall. We also planted pisonia grandis, which has a sticky fruit favoured by the seychelles white-eye, and ochrosia oppositifolia, a large tree with small white flowers.

Coconut removal

Coconuts are meant to live at the water’s edge; coconuts fall down, roll into the sea and are carried off somewhere to grow. When coconuts don’t live near water, like if you farmed them and put them on a plateau, their coconuts fall straight down and go nowhere. Then they start to grow, so beneath every coconut tree you get 100 new coconut trees. This is a problem when you want to eradicate all the coconuts.

You can’t simply remove the coconut trees either; young trees that are being planted need protection from the hot equatorial sun, which the coconuts can provide. A careful balance must be met: the coconut trees must be left until other trees around them are sufficiently large and no longer need any shade. So in the meantime, the coconuts fall, the coconuts grow and the coconuts need pulling out.

Removing a coconut that’s taken root is surprisingly fun. The first attempt is to grab the coconut by its strong leaves and pull hard, often the plant, coconut and roots will come up easily. If that fails, my preferred method is to kick the coconut repetitively with my heel until the roots come free and it can be removed; it’s therapeutic.

When you’ve created a big enough pile of coconuts, its time to load up a gator and take them to the pit, where they’ll get munched up and turned into something that can be re-used.

Pulling out coconuts means walking amongst the dead leaves and undersides of trees, there’s nothing really in the dead leaves to be worried about, there’s a rare giant centipede, but otherwise it’s just skink lizards that scuttle away when you get too close. The bigger problem is what hangs between the trees; giant palm spiders (about the size of my hand) craft invisible webs between trunks, leaves and stems, then they sit in the middle waiting for prey to get stuck. While wandering around, eyes looking down, searching for coconuts, it’s easy to walk into these beasts, or more commonly, to find your self face to face with one about an inch from your nose.

Insect surveys

The timetable says insect sorting and identification, however there weren’t any insects to sort or identify, so we didn’t do this activity as-is. There was however some new survey methods being trialled; which we did help with, somewhat.

It involved finding a particular set of waypoints using the GPS, they represented a variety of the soil types found on the island. At each point we dug a small hole and placed an open topped urine sample cup inside, filling with one third water and a squirt of washing up liquid (“sunshine” it’s called here). The sunshine prevents insects from escaping their soapy death.

In a few days time the cups would be removed, the decaying putrid mix cleaned up with ethanol, the bugs split out from the soil, put into separate vials and identified under a microscope. Matt the intern did most of this.

Indian Myna eradication

While not a volunteer activity for me, this was a big conservation project taking place while I was there. And yes, eradication means killing.

The Indian Myna bird is an invasive species, originally introduced to help catch bugs when the island was a coconut plantation. They are aggressive birds and actively harass many struggling endemic species; for instance the seychelles warbler; the myna will attack the bird and peck its head, causing brain damage, and it will turf out eggs from its nest. To encourage sea bird species to return, and to begin reintroduction programmes for other at risk birds, the mynas must first be removed. It’s not logistically possible to remove them from the island and take them somewhere else; they are humanely killed instead.

This project has its own dedicated volunteers, two students – Dyllis and Krystel for one month, and now two new volunteers, Jeremy and Maxine, who will continue the work for a further 6 months.