Finding green turtles

Finding green turtles

Green turtles only emerge at night, so seeing them requires dedication. You can’t be sure when or where a turtle might emerge, but after a week or so of recording tracks we could determine their favourite places. Then it’s a case of visiting at night, or early morning and either patrolling, or choosing your spot, getting comfortable and waiting.

We did this a number of times, usually from 9pm til about midnight, but sometimes at 5am. It requires some co-ordination to get a buggy and let security know. Being on a deserted beach, at night, in the warm night air with the stars all around you, it’s quite a beautiful place to sit and wait the night away, unless of course a crab gets too close, which happens. I often listened to music and watched falling stars.

My first turtle

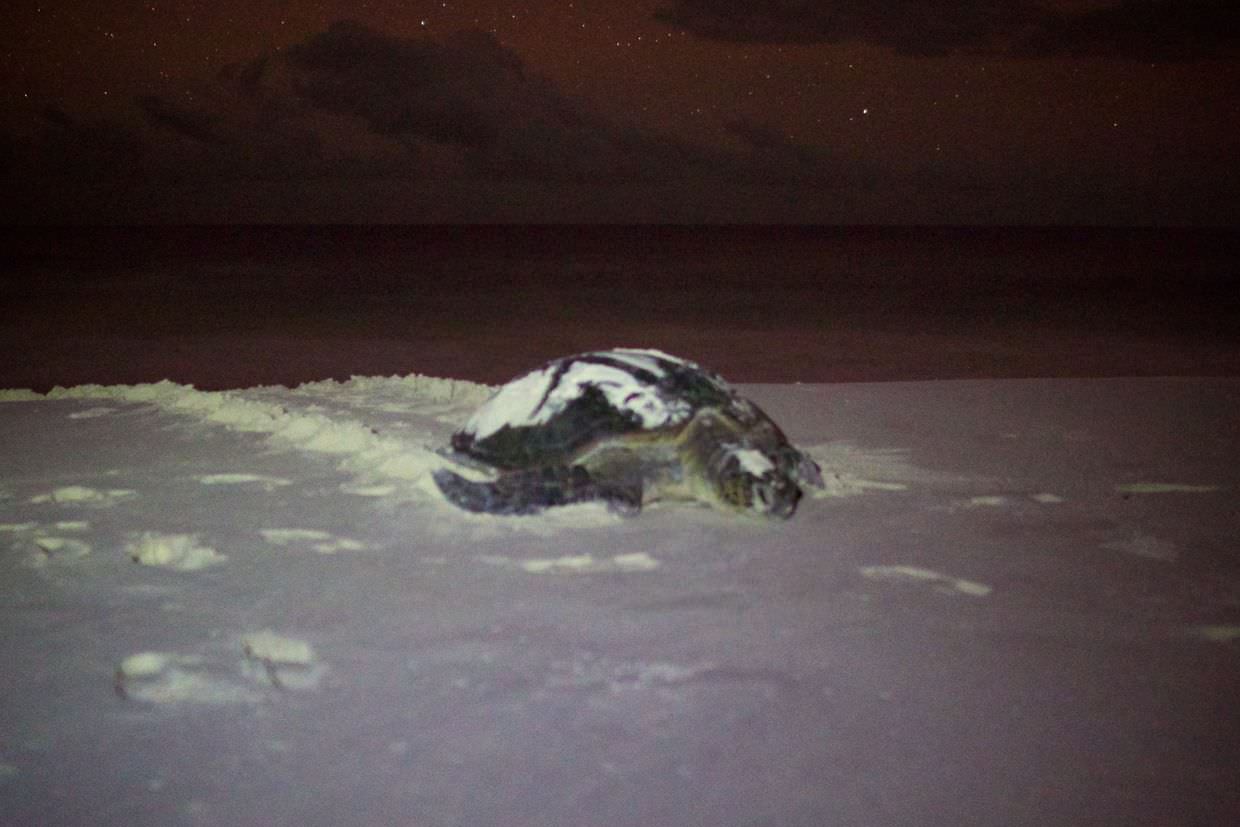

After an evening of star photography (the milky way is astounding here), I joined Robyn and we sat on west beach and we waited. Beneath the moonlight and stars, we watched for the emergence of a vague dark object from the ocean depths, like witnessing an ancient ritual we don’t fully comprehend. For hours we watched the waves, every coconut or rock starts to look like a turtle. We didn’t see anything so headed to Honeymoon beach to try our luck there, no turtles.

At 10:30pm we were going to call it a night, but now that the guests had left Sunset Bar, it was worth looking here too. Walking along the beach we heard a distant noise, it sounded like something was digging or pushing sand, and we were immediately excited. Following the sea along the beach we found a turtle trail, which didn’t have a return path – it was definitely a turtle and it was definitely still on the beach.

Green turtles are sensitive to light, so we didn’t use torches or flash photography. Typically the moon had now set, so there was complete darkness. The only light was coming from the milky way high above us, the shining heart of our galaxy illuminating nature doing its thing. Above the turtle three shooting stars passed by.

From the trail we listened intently for the turtle’s activity, the digging had stopped as soon as we arrived. We hoped this meant it was laying, we followed the tracks up the beach, stopping short of the vegetation and keeping a respectful distance, as we’d been told. We didn’t want to disturb the turtle, it needed to finish its laying and then disguise the eggs. We waited patiently, without moving, for an hour as it pushed sand about, with the occasional noise of her smacking a coconut. In the complete darkness the crabs couldn’t see us, one particularly large one inched closer, we had a coconut to scare it away, just in case.

Without any warning, a large dark object appeared from the vegetation and begun moving toward us. We kept our lights off and strained our eyes to see this magnificent creature. It edged ever closer to me, and passed to my left within 2m, stopping to rest right besides me, for a moment it looked at me, inquisitively, then it carried on, 2 strokes then rest, 2 strokes then rest, all the way down to the sea. We quietly followed it, sticking to its blind spots, and watched as it swum away, another shooting star punctuated its disappearance. A wild experience.

Turtle beneath the scaevola

The second turtle sighting was less poetic, but then there were 5 of us, rather than 2. At 9pm Robyn, Lea, Maxine, Jeremy and I started a patrol of west beach. The tide had recently gone out, and as we walked, our movement in the sand triggered little bioluminescent plankton to shine. I picked some up and walked with it in my hands, a mini beacon, like holding fairy dust.

While I was examining the magical plankton, Lea who’d gone on ahead, came running back to us, “there’s a turtle” she whispered in her german accent. We rushed to see it, and sure enough, there was a single track, and the sound of digging deep beneath a scaevola plant. We called Tarryn, and hoped perhaps we’d be able to tag this turtle, and then we waited.

Soon the digging stopped, and we edged closer to try and identify if the turtle was laying – but we couldn’t see through the foliage. Before CJ, Tarryn or Elliot had arrived, there was digging and scratching again, and without warning, after we’d been there for 40 minutes, the turtle emerged on the beach and began returning to the sea, moving swiftly and with more urgency than the previous turtle, disappearing just as Elliot arrived with the gear.

We were back at home by 10pm, an efficient night of turtle watching. The next morning’s patrols showed that no other turtles emerged in the night.

Night of the green turtles

On my penultimate night on North Island I saw more turtles, I saved the best until last. After an evening playing pool doubles at the bistro, using sawn-off cues – Jude and I vs Robyn and Maxine, pimp my ride was showing on MTV on the TV above us; and after unceremoniously losing, I returned to the volunteer house. I messaged CJ to ask if I could take the buggy out to West Beach, by myself this time, the pool victors continued playing on the table. I hadn’t yet scratched my turtle itch and wanted one last attempt.

The morning’s patrol showed that three turtles had emerged the night before, close to sunset bar and the picnic spot, or what’s known as “the sala”. None of those turtles laid, for whatever reason each of them abandoned their digs and returned to the sea. Elliot had told us that if a turtle fails to lay then it usually returns the following night, to try again. So I tried my luck.

A turtle on the run

No sooner than I arrived at the sala, at about 9pm, did I find a turtle track coming up from the sea, and then I heard digging, my heart began to beat faster. As with all the other turtle sightings, tonight there was no moon, it was a beautiful clear sky and the milky way was showing prominently, but there was no light to see by. Carefully following the track, I tried to see where she was, but I looked in the wrong place; when the next swoosh of sand emanated from the turtle, startled, I saw she was in a body pit right behind me. I called CJ and waited down the beach, hoping he’d get here in time.

This time around I really hoped I’d be able to tag the turtle. But it looked like events were about to repeat themselves, after 15 minutes, before CJ arrived, the turtle was beginning to leave, it had abandoned its dig and was heading for the sea. There was a flash of red light from the scaevola, CJ was here with the turtle gear – the bag, GPS recorder, titanium metal tags, etc. Before she returned to the sea, we’d at least need to check her for existing metal tags.

Titanium metal tags are attached to both the left and right flipper, in a fleshy part, beside their armpit. CJ started by trying to hold her flipper, but she moved them too often, and too strongly to see in the dark. Just a few metres from the water’s edge, we needed to hold her back so we could get a good look, always conscious of not stressing the animal too much.

Stopping a 170kg green turtle is not easy. We first tried pushing against her shell from the front, one of us on either side, but that was not enough and she continued onwards, pushing us aside. CJ could see that her right tag was missing, torn off, with a tag scar, but her left one was still there, if only we could read it. I moved in front of the turtle and sat down in the wet sand – a barrier, she stopped, unsure of where to go. She stopped for long enough for us to read the tag. SCA9246, “she’s one of ours”, CJ said.

Before I could move she turned inwards, back towards the beach, and in doing so she launched a flipper full of sand into my face and mouth. As I write this I still have granules of sand in my teeth. Sand gets everywhere. She hissed too, it sounded like the noise a tortoise makes when it’s scared. We tried in vain to direct her back towards the water, but she continued on her new course up the beach. We backed off to see what she’d do next, there was no need to cause any further stress.

Her behaviour now was odd. It’s as if she’d thought, “oh, I’m on the beach, what was I doing on the beach? oh yes, I need to lay eggs” – and with that she returned to her earlier dig site and continued to dig. If she did begin to lay we wouldn’t replace the missing tag, “we’ve manhandled her enough”, CJ said. We parked ourselves by the sala and photographed the stars as we waited to see what would happen.

There’s another one

While waiting for turtle 1 to lay, I wandered up the beach, towards the bar. Halfway up the beach there was a dark object. The object had a trail behind it, and it was moving towards the line of scaevola. Another turtle had arrived, and the first one I’d seen appear from the sea. “CJ, there’s another one”. “It’s going to be a late one”, he replied. And we waited. What incredible luck.

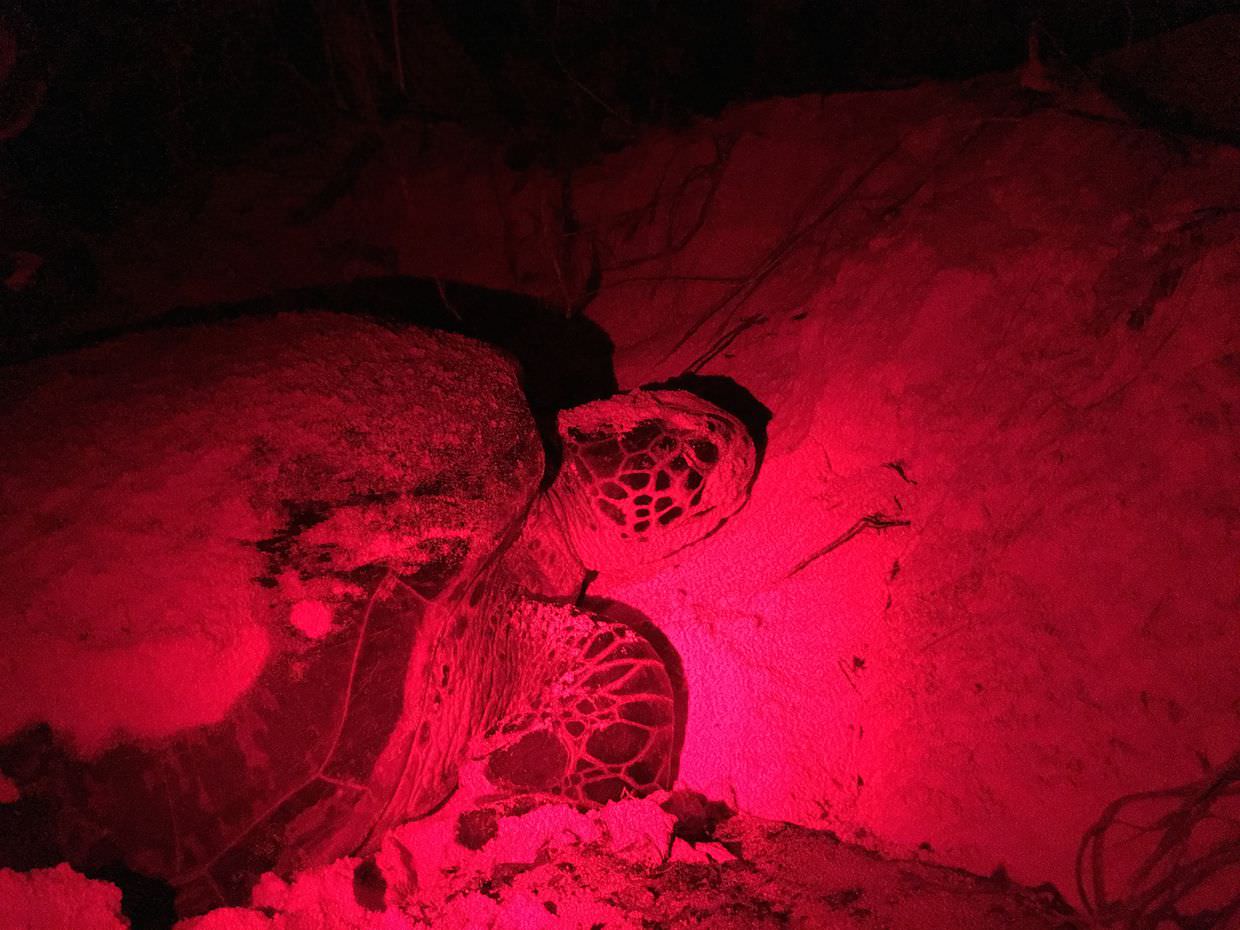

After all the prior events, turtle 1 did begin to lay, and turtle 2 had begun to dig. Now she was laying she’d entered a trance like state, and would continue to lay eggs until she was finished. This was an opportunity to get close, and to see the egg laying process. From above I could see the body pit, and the nest chamber she’d scooped out with her rear flippers, a small hole just beneath the bottom of her carapace. Into it she was laying soft white eggs, one on top of another. It was exciting, so exciting that both CJ and I managed to simultaneously drop our cameras in the sand.

Turtle 1 left a track 117cm across, and she had a carapace length of 115cm – from the top of the shell, near her head, to the tail. The pit she’d dug herself was enormous, and very deep, quite impressive. We let her finish laying, and waited for turtle 2 to do her thing.

But turtle 2 was in no rush. She’d gone to a part of the beach where the sand was soft. Previous digs here had been abandoned because the sand would keep falling back into the hole, making it impossible to dig a chamber deep enough. And as expected, she abandoned her dig, headed along the beach some more and started again. “At least another hour”, CJ said.

After half an hour we checked up on her again. More odd turtle behaviour, she had returned to her original dig site and continued digging there. None of the turtle tracks I’d seen in any of the turtle patrols that month had shown this behaviour – it was always dig and move on, dig and move on. Now we had two turtles going back to a hole they’d abandoned.

I glanced over to turtle 1, a turtle was moving near a coconut tree besides her nest, it looked like she was finished and at last returning to the sea. 20 minutes later, while idly waiting for turtle 2 to begin laying, I wandered over there. The tracks didn’t make sense, there was the original inbound track, and the loop where turtle 1 had returned after we’d stopped her, but there was another track, a new one, and that too was going up the beach. Cue turtle 3.

A turtle to tag

We now had three turtles on the beach simultaneously. Turtle 1 was covering over her nest, turtle 2 had just begun laying, and newly arrived turtle 3 was digging right beside where we’d parked ourselves, beneath a sandy ledge. This was simply amazing, an unbelievable sight.

Now that turtle 2 was laying we could check her for tags and take measurements. Measuring her carapace was tricky, the sand was so soft that lying down on it could cause the hole to collapse, which would be disastrous for the turtle and eggs. As delicately as I could, arm outstretched, I held the measure tape to her shell, as CJ moved around to take the top measurement. She left a track 112cm across, and her carapace was 117cm long. She wasn’t tagged, but with the sand this soft we couldn’t risk tagging her.

I’d been told that turtles have a distinctive smell, when Matt saw one coming up the beach he said, “you smell her first”. With the first three turtles I’d seen I hadn’t noticed a smell, CJ reminded me about it and I took a good whiff. It’s an odd smell, it’s a smell that’s wholly of the sea, but it’s not fishy, it’s altogether something else, and yes, distinct. Perhaps its uniqueness is why my brain hadn’t registered it before.

The facial features of a turtle, the pattern of scales on their faces, is unique and can be used to identify turtles in the future. We couldn’t tag her, but we could photograph her face for future reference. Using my phone and a red torch, we took a photo of her side-on, before letting her finish laying.

Turtle 1 did now eventually leave, but turtle 3 was taking her time. A conscientious digger, she spent over an hour digging a body pit and nest chamber. We thought she was almost done, but each time we checked, every 5 minutes, she was excavating her nest chamber a little more. Finally, at 1am, she began to lay. That’s 3 turtles in one session, and each of them was laying, all on a single stretch of sand.

Turtle 3 wasn’t tagged either, and she was laying in the perfect spot, we could get to both flippers. CJ pulled tags SCA9251 and SCA9250 from the bag, along with some gnarly looking pliers. The tags are about a centimetre across, and 5cm long, with a bend at the end and a spike; the spike pierces through the turtle’s skin and plugs into a hole on the other side, keeping the tag in place. To be honest they look brutal, but they need to be sturdy to survive.

CJ would do the tagging, he placed a tag between the pliers and we approached turtle 3’s left flipper first. I used my iPhone as a torch, on which I also recorded the events. CJ carefully pulled our her flipper and found the fleshy part of her armpit; poised with the pliers, “1, 2 … 3” – the pliers closed shut, the tag pierced the skin and the turtle flinched, but only slightly; her flipper was successfully tagged.

We did the same on her right flipper, then proceeded with track and carapace measurements, as well as GPS points. We took a couple of quick pictures, and then let her be, let them all be, at 1:30am we were tired, a good job done and time for bed.

Driving the buggy in the dark, lights on, all the way back, if you could see my face in the faint light you would have seen the biggest smile.